Chapter2 Setting Out

Approaches to the Qur’an

It would probably be better to delay this discussion for the appendices, so as not to lose many readers before even getting started, because I expect that the majority will be Muslims and that many of them find this subject upsetting. It has to do with the role of symbolism in revelation. The appendices may be more appropriate, because the main conclusions reached in this chapter will hardly be affected by these remarks, but my principle concern is with a smaller readership, which, while attempting to reconcile religion with modern thought, might be dissuaded by its own excessive literalism.

Muslims assert that the Qur’an is a revelation appropriate for all persons, times, and places, and it is not difficult to summon Qur’anic verses to support this claim. If they held to the opposite, there would not be much point in considering their scripture. In order to entertain this premise sincerely, we certainly should allow for, even anticipate, that the Qur’an would use allegory, parables, and other literary devices to reach a diverse audience. The language of the Qur’an would have to be that of the Prophet’s milieu and reflect the intellectual, religious, social, and material customs of the seventh-century Arabs. But if the essential message is universal, then it must transcend the very language and culture that was the vehicle of revelation. Since a community’s language grows with and out of its experiences, how then are realities outside that experience communicated? There appears to be only one avenue: through the employment of allegory, that is, the expression of truths through symbolic figures and actions or, as the famous Qur’an exegete Zamakhshari put it, “a parabolic illustration, by means of something which we know from our experience, of something that is beyond the reach of our perception. [1]

For example, the Qur’an informs us that Paradise in the hereafter is such that “no person knows what delights of the eye are kept hidden from them as a reward for their deeds” (32: 17). Yet it also provides very sensual images of Paradise that are particularly suited to the imagination of Muhammad’s contemporaries. These descriptions recall the luxury and sensual delights of the most wealthy seventh-century Bedouin chieftains. If the reader happened to be a man from Alaska, he may be quite apathetic to these enticements. He may prefer warm sandy beaches to cool oases; sunshine to constant shade; scantily clad bathing beauties to houris, with the issue of whether or not they are virgins of no real consequence. This reader will probably take these references symbolically, reinforced by the Qur’an’s frequent assignment of the word mathal (likeness, similitude, example) to its eschatological descriptions.

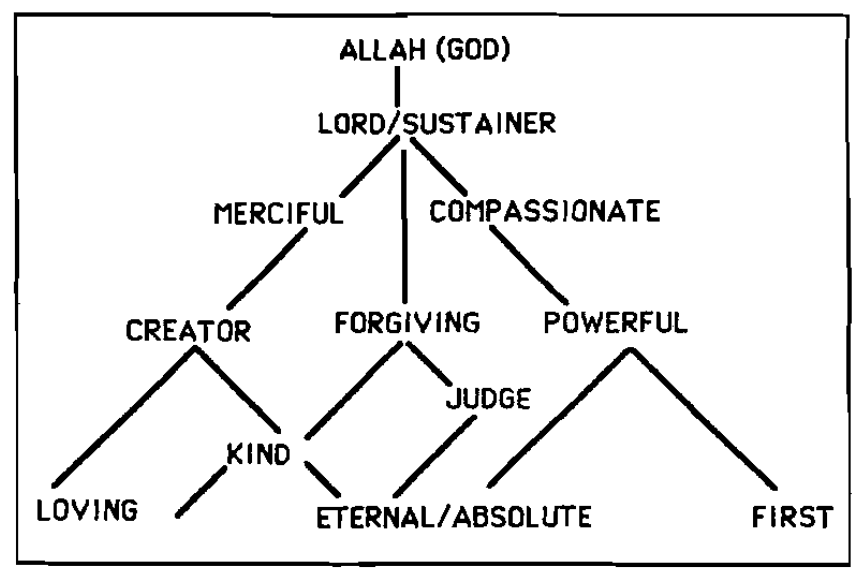

Similarly, though God is “sublimely exalted above anything that men may devise by way of definition” (6:100) and “there is nothing like unto Him” (42:11) and “nothing can be compared to Him” (112:4), the reader nonetheless needs to relate to God and His activity. Thus we find that the Qur’an provides many comparative descriptions of God. For instance, while human beings are sometimes merciful, compassionate, generous, wise and forgiving, God is The Merciful, The Compassionate, The Generous, The Wise, and The Forgiving. The Qur’an mentions God’s “face”, “hand”, “throne” and other expressions

which at first sight have an almost anthropomorphic hue, for instance, God’s “wrath” (ghadab) or “condemnation”; His “pleasure” at good deeds or “love” for His creatures; or His being “oblivious” of a sinner who was oblivious of Him; or “asking” a wrongdoer on Resurrection Day about his wrongdoing; and so forth," [2]

To disallow the possibility of symbolism in such expressions would seem to imply contradictions between some statements in the Qur’an. To do so is entirely unnecessary, especially in consideration of the following key assertion:

He it is Who has bestowed upon you from on high this divine writ, containing messages clear in and of themselves (ayat muhkamat) – and these are the foundation of the divine writ – as well as others that are allegorical (mutashabihat). Now those whose hearts are given too swerving from the truth go after that pan of it which has been expressed in allegory, seeking out confusion, and seeking its final meaning, but none save God knows its final meaning. (3:7)

Therefore the Qur’an itself insists on its use of symbolism, because to describe the realm of realities beyond human perception – what the Qur’an designates as al ghayb (the unseen or imperceptible) – would be impossible otherwise. This is why it would be a mistake to insist on assigning a literal interpretation to the Qur’an’s descriptions of God’s attributes, the Day of Judgment, Heaven and Hell, etc., because the ayat mutashabihat do not fully define and explicate these, but they relate to us, due to the limitations of human thought and language, something similar. This helps explain the well-known doctrine of bila kayf (without how) of al Ash’ari, the famous tenth-century theologian whose viewpoint on this matter became dominant in Muslim thought. It states that such verses reveal truths, but we should not insist on, or ask, how these truths are realized. [3]

Throughout Muslim history, the literalist trend in Qur’an exegesis was one among a number of approaches. Today, in America and Canada, it has emerged as the most prevalent. It appears that the majority of Muslim lecturers in America tend to take every narrative or description in the Qur’an as a statement of a scientific or historical fact. So, for example, the story of Adam is assumed to relate the historical and scientific origins of Homo Sapiens. This tendency is reinforced by the current widespread excitement over recent Qur’an and Science studies, where many, if not most, of the discoveries of modern science are believed to have been anticipated by the Qur’an.

It is true that some of the descriptions in the Qur’an of the “signs” (ayat) in nature of God’s wisdom and beneficence bear a fascinating resemblance to certain modem discoveries, and it is also true that none of these signs can be proved to be in conflict with science. But part of the reason for this may argue against attempts by Muslims to subject the Qur’an to scientific scrutiny. [4] The Qur’an is very far from being a science textbook. Its language is of the highest literary quality and open to many different shades of meaning. The descriptions of many of the Qur’an’s signs that are believed today to predict recently established facts appear to be consistently and intentionally ambiguous, avoiding a degree of explicitness that would conflict with any reader’s level of knowledge of whatever era. If the Qur’an contained a precise elaboration of these phenomena (the big bang theory, the splitting of the atom, the expansion of the universe, to name a few), these would have been known to ancient Muslim scientists. A truly wondrous feature of the Qur’an is that these signs lose nothing of their power, beauty, and mystery from one generation to the next; each generation has found them compatible with the current state of knowledge. To be inspired with awe and wonder by the Qur’anic signs is one thing; to attempt to deduce or impose upon them scientific theories is another and, moreover, is contrary to the Qur’an’s style.

The relationship between the Qur’an and history is very much the same. Anyone familiar with the Bible will notice that there are many narratives in the Qur’an that have Biblical parallels. In the past, Orientalists would accuse Muhammad, whom they assumed to be the Qur’an’s author, of plagiarizing or borrowing material from Jewish and Christian sources. This opinion has become increasingly unpopular among western scholars of Islam. For one thing, where Biblical parallels do exist, the Qur’anic accounts almost always involve many key differences in detail and meaning. Equally important is the fact that the Qur’an itself assumes that its initial hearers were fairly well acquainted with these tales. It is therefore very probable that through centuries of contact, Jews, Christians, and pagans of the Arabian peninsula adopted, with modifications, each other’s oral traditions. It also would not be at all surprising that traditions shared by Jews and Arabs of the Middle East would go back to a common source, since they shared a common ancestry. Hence, the conjecture that the Qur’an borrows from the Bible is inappropriate.

In addition to biblical parallels, the Qur’an contains a number of stories that were apparently known only to the Arabian peninsula and at least one of mysterious origins.[5] A striking difference between all of the Qur’anic accounts and the biblical narratives is that while the latter are very often presented in a historical setting, the former defy all attempts to do so, unless outside sources are consulted. In other words, relying exclusively on the Qur’an, it is nearly impossible to place these stories in history. The episodes are told in such a way that the meaning behind the story is emphasized while extraneous details are omitted. Thus, western readers who know nothing of the Arabian tribes of ’Ad and Thamud readily understand the moral behind their tales. This omission of historical detail adds to the transcendent and universal appeal of the narratives, for it helps the reader focus on the timeless meaning of the stories.

The Qur’anic stories are so utterly devoid of historical reference points that it is not always clear whether a given account is meant to be taken as history, a parable, or an allegory. Consider the following two verses from the story of Adam:

It is We Who created you, then We gave you shape, then We bade the angels, “Bow down to Adam!” and they bowed down; not so Iblis; he refused to be of those who bow down. (7:11)

And when your Lord drew forth from the children of Adam, from their loins, their seed, and made them testify of themselves, (saying) “Am I not your Lord?” They said, “Yes, truly we testify.” (That was) lest you should say on the Day of Resurrection: “Lo! of this we were unaware.” (7:172)

Note the transition in 7:11 from “you” (plural in Arabic) in the first two clauses to “Adam” in the third, as if mankind is being identified with Adam. These verses seem to demand symbolic interpretations, otherwise from the first we would have to conclude that we were created, then we were given shape, then the command was given concerning the first man! As for 7:172, I would not even know how to begin to interpret this verse concretely, and it should come as no surprise that many ancient commentators also understood it symbolically.

The Qur’an’s eighteenth surah, al Kahf, relates a number of beautiful stories in an almost surrealistic style. For example, verse 86, from the tale of Dhul Qarnain reads,

Until, when he reached the setting of the sun, and he found it setting in a muddy spring, and found a people near it. We said: “O Dhul Qarnain! Either punish them or treat them with kindness.” (18:86)

This verse has puzzled Muslim commentators, many of whom searched history for a great prophet conqueror that might compare to Dhul Qarnain, who reached the lands where the sun rises and sets. The most popular choice was Alexander the Great, which is patently false since he is well known to have been a pagan. Since the sun does not literally set in a muddy spring with people nearby, a less-than-literal interpretation is forced upon us.

Rather than belabor the point, let me summarize my position. On the basis of the style and character of the Qur’an, I believe that the most general and most cautious statement one can make is: The Qur’an relates many stories, versions with which the Arabs were apparently somewhat familiar, not for the sake of relating history or satisfying human curiosity, but to “draw a moral, illustrate a point, sharpen the focus of attention, and to reinforce the basic message.” [6] I would advise against attempts to force or decide the historicity of each of these stories. First of all, because the Qur’an avoids historical landmarks and since certain passages in some narratives clearly can not be taken literally, such an insistence seems unwarranted. Furthermore, imposing such limitations on the Qur’an may lead, unnecessarily, to rational conflicts and obstructions that distract the reader from the moral of a given tale. The Qur’an itself harshly criticizes this inclination in Surat al Kahf:

Some say they were three, the dog being the fourth among them. Others say they were five, the dog being the sixth – doubtfully guessing at the unknown. Yet others say seven, the dog being the eighth. Say, “My Lord knows best their number, and none knows them, but a few. Therefore, do not enter into controversies concerning them, except on a matter that is clear.” (18:22)

Moreover, it would be humanly impossible to definitively decide the historic or symbolic character of every tale; no one has the requisite level of knowledge of history and Arab oral tradition – not to mention insight into the intent and wisdom of the author – to make such a claim. Personal ignorance should be admitted, but it should not be allowed to place limits and bounds on the ways and means of revelation.

As we set out on our journey, we will be approaching the Qur’an from the standpoint of meaning; seeking to make sense of and find purpose in the existence of God, man, and life. We are now ready to embark. We have made our preparations and have broken camp. With the Qur’an before us, we enter the first page.

Muhammad Asad, The Message of the Qur’an (Gibraltar: Dar al Andalus, 1980), 989-91. ↩︎

Ibid ↩︎

Annemarie Schimmel, Islam, An Introduction (New York: SUNY Press, 1992), 78-81. ↩︎

See for example, Malik Bennabi, The Qur’anic Phenomenon,

trans. by A.B. Kirkary (Plainfield, IN: American Trust Publications,

1983); Maurice Bucaille, The Bible, the Qur’an and Science (Paris:

Seghers Publishers, 1977); and Keith L. Moore, The Developing Human

(appendix to 3d edition) (Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1982). As

I remarked in Struggling to Surrender, this topic is interesting and

sometimes fascinating, but it too often requires complicated and

unobvious extrapolati…s in interpreting certain words and phrases.

This trend exists in other religious communities as well. A speaker

informed his audience that the New Testament contains the big bang

theory of creation, for in John it states that in the beginning was

the “word”. Since a word is a single entity in the universe of

language that when voiced produces a vibration of sound, we obtain by

some isomorphism to the physical universe the theory of a single

original point mass of infinite density that explodes! ↩︎See the discussion on page 14 concerning Dhul Qarnain. ↩︎

G. R. Hawting and Abdul-Kader A. Shareef, Approaches to the

Qur’an (New York: Routledge, 1993), from the article by Ismael

K. Poonawala, “Darwaza’s principles of modern exegesis,” p. 231. ↩︎